Red–black tree

|

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Type | Tree | |

| Invented | 1972 | |

| Invented by | Rudolf Bayer | |

| Time complexity in big O notation |

||

| Average | Worst case | |

| Space | O(n) | O(n) |

| Search | O(log n) | O(log n) |

| Insert | O(log n) | O(log n) |

| Delete | O(log n) | O(log n) |

A red–black tree is a type of self-balancing binary search tree, a data structure used in computer science, typically to implement associative arrays. The original structure was invented in 1972 by Rudolf Bayer[1] and named "symmetric binary B-tree," but acquired its modern name in a paper in 1978 by Leonidas J. Guibas and Robert Sedgewick.[2] It is complex, but has good worst-case running time for its operations and is efficient in practice: it can search, insert, and delete in O(log n) time, where n is the total number of elements in the tree. Put very simply, a red–black tree is a binary search tree that inserts and deletes in such a way that the tree is always reasonably balanced.

Contents |

Terminology

A red–black tree is a special type of binary tree, used in computer science to organize pieces of comparable data, such as text fragments or numbers.

The leaf nodes of red–black trees do not contain data. These leaves need not be explicit in computer memory — a null child pointer can encode the fact that this child is a leaf — but it simplifies some algorithms for operating on red–black trees if the leaves really are explicit nodes. To save memory, sometimes a single sentinel node performs the role of all leaf nodes; all references from internal nodes to leaf nodes then point to the sentinel node.

Red–black trees, like all binary search trees, allow efficient in-order traversal in the fashion, Left–Root–Right, of their elements. The search-time results from the traversal from root to leaf, and therefore a balanced tree, having the least possible tree height, results in O(log n) search time.

Properties

A red–black tree is a binary search tree where each node has a color attribute, the value of which is either red or black. In addition to the ordinary requirements imposed on binary search trees, the following requirements apply to red–black trees:

- A node is either red or black.

- The root is black. (This rule is sometimes omitted from other definitions. Since the root can always be changed from red to black, but not necessarily vice-versa, this rule has little effect on analysis.)

- All leaves are the same color as the root.

- Both children of every red node are black.

- Every simple path from a given node to any of its descendant leaves contains the same number of black nodes.

These constraints enforce a critical property of red–black trees: that the path from the root to the furthest leaf is no more than twice as long as the path from the root to the nearest leaf. The result is that the tree is roughly balanced. Since operations such as inserting, deleting, and finding values require worst-case time proportional to the height of the tree, this theoretical upper bound on the height allows red–black trees to be efficient in the worst-case, unlike ordinary binary search trees.

To see why this is guaranteed, it suffices to consider the effect of properties 4 and 5 together. For a red–black tree T, let B be the number of black nodes in property 5. Therefore the shortest possible path from the root of T to any leaf consists of B black nodes. Longer possible paths may be constructed by inserting red nodes. However, property 4 makes it impossible to insert more than one consecutive red node. Therefore the longest possible path consists of 2B nodes, alternating black and red.

The shortest possible path has all black nodes, and the longest possible path alternates between red and black nodes. Since all maximal paths have the same number of black nodes, by property 5, this shows that no path is more than twice as long as any other path.

In many of the presentations of tree data structures, it is possible for a node to have only one child, and leaf nodes contain data. It is possible to present red–black trees in this paradigm, but it changes several of the properties and complicates the algorithms. For this reason, this article uses "null leaves", which contain no data and merely serve to indicate where the tree ends, as shown above. These nodes are often omitted in drawings, resulting in a tree that seems to contradict the above principles, but in fact does not. A consequence of this is that all internal (non-leaf) nodes have two children, although one or both of those children may be null leaves. Property 5 ensures that a red node must have either two black null leaves or two black non-leaves as children. For a black node with one null leaf child and one non-null-leaf child, properties 3, 4 and 5 ensure that the non-null-leaf child must be a red node with two black null leaves as children.

Some explain a red–black tree as a binary search tree whose edges, instead of nodes, are colored in red or black, but this does not make any difference. The color of a node in this article's terminology corresponds to the color of the edge connecting the node to its parent, except that the root node is always black (property 2) whereas the corresponding edge does not exist.

Analogy to B-trees of order 4

A red–black tree is similar in structure to a B-tree of order 4, where each node can contain between 1 to 3 values and (accordingly) between 2 to 4 child pointers. In such B-tree, each node will contain only one value matching the value in a black node of the red–black tree, with an optional value before and/or after it in the same node, both matching an equivalent red node of the red–black tree.

One way to see this equivalence is to "move up" the red nodes in a graphical representation of the red–black tree, so that they align horizontally with their parent black node, by creating together a horizontal cluster. In the B-tree, or in the modified graphical representation of the red–black tree, all leaf nodes are at the same depth.

The red–black tree is then structurally equivalent to a B-tree of order 4, with a minimum fill factor of 33% of values per cluster with a maximum capacity of 3 values.

This B-tree type is still more general than a red–black tree though, as it allows ambiguity in a red–black tree conversion—multiple red–black trees can be produced from an equivalent B-tree of order 4. If a B-tree cluster contains only 1 value, it is the minimum, black, and has two child pointers. If a cluster contains 3 values, then the central value will be black and each value stored on its sides will be red. If the cluster contains two values, however, either one can become the black node in the red–black tree (and the other one will be red).

So the order-4 B-tree does not maintain which of the values contained in each cluster is the root black tree for the whole cluster and the parent of the other values in the same cluster. Despite this, the operations on red–black trees are more economical in time because you don't have to maintain the vector of values. It may be costly if values are stored directly in each node rather than being stored by reference. B-tree nodes, however, are more economical in space because you don't need to store the color attribute for each node. Instead, you have to know which slot in the cluster vector is used. If values are stored by reference, e.g. objects, null references can be used and so the cluster can be represented by a vector containing 3 slots for value pointers plus 4 slots for child references in the tree. In that case, the B-tree can be more compact in memory, improving data locality.

The same analogy can be made with B-trees with larger orders that can be structurally equivalent to a colored binary tree: you just need more colors. Suppose that you add blue, then the blue–red–black tree defined like red–black trees but with the additional constraint that no two successive nodes in the hierarchy will be blue and all blue nodes will be children of a red node, then it becomes equivalent to a B-tree whose clusters will have at most 7 values in the following colors: blue, red, blue, black, blue, red, blue (For each cluster, there will be at most 1 black node, 2 red nodes, and 4 blue nodes).

For moderate volumes of values, insertions and deletions in a colored binary tree are faster compared to B-trees because colored trees don't attempt to maximize the fill factor of each horizontal cluster of nodes (only the minimum fill factor is guaranteed in colored binary trees, limiting the number of splits or junctions of clusters). B-trees will be faster for performing rotations (because rotations will frequently occur within the same cluster rather than with multiple separate nodes in a colored binary tree). However for storing large volumes, B-trees will be much faster as they will be more compact by grouping several children in the same cluster where they can be accessed locally.

All optimizations possible in B-trees to increase the average fill factors of clusters are possible in the equivalent multicolored binary tree. Notably, maximizing the average fill factor in a structurally equivalent B-tree is the same as reducing the total height of the multicolored tree, by increasing the number of non-black nodes. The worst case occurs when all nodes in a colored binary tree are black, the best case occurs when only a third of them are black (and the other two thirds are red nodes).

Red–black trees offer worst-case guarantees for insertion time, deletion time, and search time. Not only does this make them valuable in time-sensitive applications such as real-time applications, but it makes them valuable building blocks in other data structures which provide worst-case guarantees; for example, many data structures used in computational geometry can be based on red–black trees, and the Completely Fair Scheduler used in current Linux kernels uses red–black trees.

The AVL tree is another structure supporting O(log n) search, insertion, and removal. It is more rigidly balanced than red–black trees, leading to slower insertion and removal but faster retrieval. This makes it attractive for data structures that may be built once and loaded without reconstruction, such as language dictionaries (or program dictionaries, such as the opcodes of an assembler or interpreter).

Red–black trees are also particularly valuable in functional programming, where they are one of the most common persistent data structures, used to construct associative arrays and sets which can retain previous versions after mutations. The persistent version of red–black trees requires O(log n) space for each insertion or deletion, in addition to time.

For every 2-4 tree, there are corresponding red–black trees with data elements in the same order. The insertion and deletion operations on 2-4 trees are also equivalent to color-flipping and rotations in red–black trees. This makes 2-4 trees an important tool for understanding the logic behind red–black trees, and this is why many introductory algorithm texts introduce 2-4 trees just before red–black trees, even though 2-4 trees are not often used in practice.

In 2008, Sedgewick introduced a simpler version of red–black trees called Left-Leaning Red–Black Trees[3] by eliminating a previously unspecified degree of freedom in the implementation. The LLRB maintains an additional invariant that all red links must lean left except during inserts and deletes. Red–black trees can be made isometric to either 2-3 trees,[4] or 2-4 trees,[3] for any sequence of operations. The 2-4 tree isometry was described in 1978 by Sedgewick. With 2-4 trees, the isometry is resolved by a "color flip," corresponding to a split, in which the red color of two children nodes leaves the children and moves to the parent node. The tango tree, a type of tree optimized for fast searches, usually uses red–black trees as part of its data structure.

Operations

Read-only operations on a red–black tree require no modification from those used for binary search trees, because every red–black tree is a special case of a simple binary search tree. However, the immediate result of an insertion or removal may violate the properties of a red–black tree. Restoring the red–black properties requires a small number (O(log n) or amortized O(1)) of color changes (which are very quick in practice) and no more than three tree rotations (two for insertion). Although insert and delete operations are complicated, their times remain O(log n).

Insertion

Insertion begins by adding the node much as binary search tree insertion does and by coloring it red. Whereas in the binary search tree, we always add a leaf, in the red–black tree leaves contain no information, so instead we add a red interior node, with two black leaves, in place of an existing black leaf.

What happens next depends on the color of other nearby nodes. The term uncle node will be used to refer to the sibling of a node's parent, as in human family trees. Note that:

- property 3 (all leaves are black) always holds.

- property 4 (both children of every red node are black) is threatened only by adding a red node, repainting a black node red, or a rotation.

- property 5 (all paths from any given node to its leaf nodes contain the same number of black nodes) is threatened only by adding a black node, repainting a red node black (or vice versa), or a rotation.

- Note: The label N will be used to denote the current node (colored red). At the beginning, this is the new node being inserted, but the entire procedure may also be applied recursively to other nodes (see case 3). P will denote N's parent node, G will denote N's grandparent, and U will denote N's uncle. Note that in between some cases, the roles and labels of the nodes are exchanged, but in each case, every label continues to represent the same node it represented at the beginning of the case. Any color shown in the diagram is either assumed in its case or implied by those assumptions.

Each case will be demonstrated with example C code. The uncle and grandparent nodes can be found by these functions:

struct node *grandparent(struct node *n) { if ((n != NULL) && (n->parent != NULL)) return n->parent->parent; else return NULL; } struct node *uncle(struct node *n) { struct node *g = grandparent(n); if (g == NULL) return NULL; // No grandparent means no uncle if (n->parent == g->left) return g->right; else return g->left; }

Case 1: The current node N is at the root of the tree. In this case, it is repainted black to satisfy property 2 (the root is black). Since this adds one black node to every path at once, property 5 (all paths from any given node to its leaf nodes contain the same number of black nodes) is not violated.

void insert_case1(struct node *n) { if (n->parent == NULL) n->color = BLACK; else insert_case2(n); }

Case 2: The current node's parent P is black, so property 4 (both children of every red node are black) is not invalidated. In this case, the tree is still valid. property 5 (all paths from any given node to its leaf nodes contain the same number of black nodes) is not threatened, because the current node N has two black leaf children, but because N is red, the paths through each of its children have the same number of black nodes as the path through the leaf it replaced, which was black, and so this property remains satisfied.

void insert_case2(struct node *n) { if (n->parent->color == BLACK) return; /* Tree is still valid */ else insert_case3(n); }

- Note: In the following cases it can be assumed that N has a grandparent node G, because its parent P is red, and if it were the root, it would be black. Thus, N also has an uncle node U, although it may be a leaf in cases 4 and 5.

|

Case 3: If both the parent P and the uncle U are red, then both of them can be repainted black and the grandparent G becomes red (to maintain property 5 (all paths from any given node to its leaf nodes contain the same number of black nodes)). Now, the current red node N has a black parent. Since any path through the parent or uncle must pass through the grandparent, the number of black nodes on these paths has not changed. However, the grandparent G may now violate properties 2 (The root is black) or 4 (Both children of every red node are black) (property 4 possibly being violated since G may have a red parent). To fix this, the entire procedure is recursively performed on G from case 1. Note that this is a tail-recursive call, so it could be rewritten as a loop; since this is the only loop, and any rotations occur after this loop, this proves that a constant number of rotations occur. |

void insert_case3(struct node *n) { struct node *u = uncle(n), *g; if ((u != NULL) && (u->color == RED)) { n->parent->color = BLACK; u->color = BLACK; g = grandparent(n); g->color = RED; insert_case1(g); } else { insert_case4(n); } }

- Note: In the remaining cases, it is assumed that the parent node P is the left child of its parent. If it is the right child, left and right should be reversed throughout cases 4 and 5. The code samples take care of this.

|

case 4: The parent P is red but the uncle U is black; also, the current node N is the right child of P, and P in turn is the left child of its parent G. In this case, a left rotation that switches the roles of the current node N and its parent P can be performed; then, the former parent node P is dealt with using case 5 (relabeling N and P) because property 4 (both children of every red node are black) is still violated. The rotation causes some paths (those in the sub-tree labelled "1") to pass through the node N where they did not before. It also causes some paths (those in the sub-tree labelled "3") not to pass through the node P where they did before. However, both of these nodes are red, so property 5 (all paths from any given node to its leaf nodes contain the same number of black nodes) is not violated by the rotation. After this case has been completed, property 4 (both children of every red node are black) is still violated, but now we can resolve this by continuing to case 5. |

void insert_case4(struct node *n) { struct node *g = grandparent(n); if ((n == n->parent->right) && (n->parent == g->left)) { rotate_left(n->parent); n = n->left; } else if ((n == n->parent->left) && (n->parent == g->right)) { rotate_right(n->parent); n = n->right; } insert_case5(n); }

|

Case 5: The parent P is red but the uncle U is black, the current node N is the left child of P, and P is the left child of its parent G. In this case, a right rotation on G is performed; the result is a tree where the former parent P is now the parent of both the current node N and the former grandparent G. G is known to be black, since its former child P could not have been red otherwise (without violating property 4). Then, the colors of P and G are switched, and the resulting tree satisfies property 4 (both children of every red node are black). Property 5 (all paths from any given node to its leaf nodes contain the same number of black nodes) also remains satisfied, since all paths that went through any of these three nodes went through G before, and now they all go through P. In each case, this is the only black node of the three. |

void insert_case5(struct node *n) { struct node *g = grandparent(n); n->parent->color = BLACK; g->color = RED; if ((n == n->parent->left) && (n->parent == g->left)) { rotate_right(g); } else if ((n == n->parent->right) && (n->parent == g->right)) { rotate_left(g); } }

Note that inserting is actually in-place, since all the calls above use tail recursion.

Removal

In a regular binary search tree when deleting a node with two non-leaf children, we find either the maximum element in its left subtree (which is the in-order predecessor) or the minimum element in its right subtree (which is the in-order successor) and move its value into the node being deleted (as shown here). We then delete the node we copied the value from, which must have fewer than two non-leaf children. (Non-leaf children, rather than all children, are specified here because unlike normal binary search trees, red–black trees have leaf nodes anywhere they can have them, so that all nodes are either internal nodes with two children or leaf nodes with, by definition, zero children. In effect, internal nodes having two leaf children in a red–black tree are like the leaf nodes in a regular binary search tree.) Because merely copying a value does not violate any red–black properties, this reduces to the problem of deleting a node with at most one non-leaf child. Once we have solved that problem, the solution applies equally to the case where the node we originally want to delete has at most one non-leaf child as to the case just considered where it has two non-leaf children.

Therefore, for the remainder of this discussion we address the deletion of a node with at most one non-leaf child. We use the label M to denote the node to be deleted; C will denote a selected child of M, which we will also call "its child". If M does have a non-leaf child, call that its child, C; otherwise, choose either leaf as its child, C.

If M is a red node, we simply replace it with its child C, which must be black by property 4. (This can only occur when M has two leaf children, because if the red node M had a black non-leaf child on one side but just a leaf child on the other side, then the count of black nodes on both sides would be different, thus the tree would violate property 5.) All paths through the deleted node will simply pass through one less red node, and both the deleted node's parent and child must be black, so property 3 (all leaves are black) and property 4 (both children of every red node are black) still hold.

Another simple case is when M is black and C is red. Simply removing a black node could break Properties 4 (“Both children of every red node are black”) and 5 (“All paths from any given node to its leaf nodes contain the same number of black nodes”), but if we repaint C black, both of these properties are preserved.

The complex case is when both M and C are black. (This can only occur when deleting a black node which has two leaf children, because if the black node M had a black non-leaf child on one side but just a leaf child on the other side, then the count of black nodes on both sides would be different, thus the tree would had been an invalid red–black tree by violation of property 5.) We begin by replacing M with its child C. We will call (or label—that is, relabel) this child (in its new position) N, and its sibling (its new parent's other child) S. (S was previously the sibling of M.) In the diagrams below, we will also use P for N's new parent (M's old parent), SL for S's left child, and SR for S's right child (S cannot be a leaf because if N is black, which we presumed, then P's one subtree which includes N counts two black-height and thus P's other subtree which includes S must also count two black-height, which cannot be the case if S is a leaf node).

- Note: In between some cases, we exchange the roles and labels of the nodes, but in each case, every label continues to represent the same node it represented at the beginning of the case. Any color shown in the diagram is either assumed in its case or implied by those assumptions. White represents an unknown color (either red or black).

We will find the sibling using this function:

struct node *sibling(struct node *n) { if (n == n->parent->left) return n->parent->right; else return n->parent->left; }

- Note: In order that the tree remains well-defined, we need that every null leaf remains a leaf after all transformations (that it will not have any children). If the node we are deleting has a non-leaf (non-null) child N, it is easy to see that the property is satisfied. If, on the other hand, N would be a null leaf, it can be verified from the diagrams (or code) for all the cases that the property is satisfied as well.

We can perform the steps outlined above with the following code, where the function replace_node substitutes child into n's place in the tree. For convenience, code in this section will assume that null leaves are represented by actual node objects rather than NULL (the code in the Insertion section works with either representation).

void delete_one_child(struct node *n) { /* * Precondition: n has at most one non-null child. */ struct node *child = is_leaf(n->right) ? n->left : n->right; replace_node(n, child); if (n->color == BLACK) { if (child->color == RED) child->color = BLACK; else delete_case1(child); } free(n); }

- Note: If N is a null leaf and we do not want to represent null leaves as actual node objects, we can modify the algorithm by first calling delete_case1() on its parent (the node that we delete,

nin the code above) and deleting it afterwards. We can do this because the parent is black, so it behaves in the same way as a null leaf (and is sometimes called a 'phantom' leaf). And we can safely delete it at the end asnwill remain a leaf after all operations, as shown above.

If both N and its original parent are black, then deleting this original parent causes paths which proceed through N to have one fewer black node than paths that do not. As this violates property 5 (all paths from any given node to its leaf nodes contain the same number of black nodes), the tree must be rebalanced. There are several cases to consider:

Case 1: N is the new root. In this case, we are done. We removed one black node from every path, and the new root is black, so the properties are preserved.

void delete_case1(struct node *n) { if (n->parent != NULL) delete_case2(n); }

- Note: In cases 2, 5, and 6, we assume N is the left child of its parent P. If it is the right child, left and right should be reversed throughout these three cases. Again, the code examples take both cases into account.

|

Case 2: S is red. In this case we reverse the colors of P and S, and then rotate left at P, turning S into N's grandparent. Note that P has to be black as it had a red child. Although all paths still have the same number of black nodes, now N has a black sibling and a red parent, so we can proceed to step 4, 5, or 6. (Its new sibling is black because it was once the child of the red S.) In later cases, we will relabel N's new sibling as S. |

void delete_case2(struct node *n) { struct node *s = sibling(n); if (s->color == RED) { n->parent->color = RED; s->color = BLACK; if (n == n->parent->left) rotate_left(n->parent); else rotate_right(n->parent); } delete_case3(n); }

|

Case 3: P, S, and S's children are black. In this case, we simply repaint S red. The result is that all paths passing through S, which are precisely those paths not passing through N, have one less black node. Because deleting N's original parent made all paths passing through N have one less black node, this evens things up. However, all paths through P now have one fewer black node than paths that do not pass through P, so property 5 (all paths from any given node to its leaf nodes contain the same number of black nodes) is still violated. To correct this, we perform the rebalancing procedure on P, starting at case 1. |

void delete_case3(struct node *n) { struct node *s = sibling(n); if ((n->parent->color == BLACK) && (s->color == BLACK) && (s->left->color == BLACK) && (s->right->color == BLACK)) { s->color = RED; delete_case1(n->parent); } else delete_case4(n); }

|

Case 4: S and S's children are black, but P is red. In this case, we simply exchange the colors of S and P. This does not affect the number of black nodes on paths going through S, but it does add one to the number of black nodes on paths going through N, making up for the deleted black node on those paths. |

void delete_case4(struct node *n) { struct node *s = sibling(n); if ((n->parent->color == RED) && (s->color == BLACK) && (s->left->color == BLACK) && (s->right->color == BLACK)) { s->color = RED; n->parent->color = BLACK; } else delete_case5(n); }

|

Case 5: S is black, S's left child is red, S's right child is black, and N is the left child of its parent. In this case we rotate right at S, so that S's left child becomes S's parent and N's new sibling. We then exchange the colors of S and its new parent. All paths still have the same number of black nodes, but now N has a black sibling whose right child is red, so we fall into case 6. Neither N nor its parent are affected by this transformation. (Again, for case 6, we relabel N's new sibling as S.) |

void delete_case5(struct node *n) { struct node *s = sibling(n); if (s->color == BLACK) { /* this if statement is trivial, due to case 2 (even though case 2 changed the sibling to a sibling's child, the sibling's child can't be red, since no red parent can have a red child). */ /* the following statements just force the red to be on the left of the left of the parent, or right of the right, so case six will rotate correctly. */ if ((n == n->parent->left) && (s->right->color == BLACK) && (s->left->color == RED)) { /* this last test is trivial too due to cases 2-4. */ s->color = RED; s->left->color = BLACK; rotate_right(s); } else if ((n == n->parent->right) && (s->left->color == BLACK) && (s->right->color == RED)) {/* this last test is trivial too due to cases 2-4. */ s->color = RED; s->right->color = BLACK; rotate_left(s); } } delete_case6(n); }

|

Case 6: S is black, S's right child is red, and N is the left child of its parent P. In this case we rotate left at P, so that S becomes the parent of P and S's right child. We then exchange the colors of P and S, and make S's right child black. The subtree still has the same color at its root, so Properties 4 (Both children of every red node are black) and 5 (All paths from any given node to its leaf nodes contain the same number of black nodes) are not violated. However, N now has one additional black ancestor: either P has become black, or it was black and S was added as a black grandparent. Thus, the paths passing through N pass through one additional black node. Meanwhile, if a path does not go through N, then there are two possibilities:

Either way, the number of black nodes on these paths does not change. Thus, we have restored Properties 4 (Both children of every red node are black) and 5 (All paths from any given node to its leaf nodes contain the same number of black nodes). The white node in the diagram can be either red or black, but must refer to the same color both before and after the transformation. |

void delete_case6(struct node *n) { struct node *s = sibling(n); s->color = n->parent->color; n->parent->color = BLACK; if (n == n->parent->left) { s->right->color = BLACK; rotate_left(n->parent); } else { s->left->color = BLACK; rotate_right(n->parent); } }

Again, the function calls all use tail recursion, so the algorithm is in-place. In the algorithm above, all cases are chained in order, except in delete case 3 where it can recurse to case 1 back to the parent node: this is the only case where an in-place implementation will effectively loop (after only one rotation in case 3).

Additionally, no tail recursion ever occurs on a child node, so the tail recursion loop can only move from a child back to its successive ancestors. No more than O(log n) loops back to case 1 will occur (where n is the total number of nodes in the tree before deletion). If a rotation occurs in case 2 (which is the only possibility of rotation within the loop of cases 1–3), then the parent of the node N becomes red after the rotation and we will exit the loop. Therefore at most one rotation will occur within this loop. Since no more than two additional rotations will occur after exiting the loop, at most three rotations occur in total.

Proof of asymptotic bounds

A red black tree which contains n internal nodes has a height of O(log(n)).

Definitions:

- h(v) = height of subtree rooted at node v

- bh(v) = the number of black nodes (not counting v if it is black) from v to any leaf in the subtree (called the black-height).

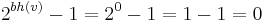

Lemma: A subtree rooted at node v has at least  internal nodes.

internal nodes.

Proof of Lemma (by induction height):

Basis: h(v) = 0

If v has a height of zero then it must be null, therefore bh(v) = 0. So:

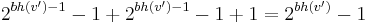

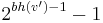

Inductive Step: v such that h(v) = k, has at least  internal nodes implies that

internal nodes implies that  such that h(

such that h( ) = k+1 has at least

) = k+1 has at least  internal nodes.

internal nodes.

Since  has h(

has h( ) > 0 it is an internal node. As such it has two children each of which have a black-height of either bh(

) > 0 it is an internal node. As such it has two children each of which have a black-height of either bh( ) or bh(

) or bh( )-1 (depending on whether the child is red or black, respectively). By the inductive hypothesis each child has at least

)-1 (depending on whether the child is red or black, respectively). By the inductive hypothesis each child has at least  internal nodes, so

internal nodes, so  has at least:

has at least:

internal nodes.

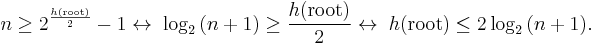

Using this lemma we can now show that the height of the tree is logarithmic. Since at least half of the nodes on any path from the root to a leaf are black (property 4 of a red–black tree), the black-height of the root is at least h(root)/2. By the lemma we get:

Therefore the height of the root is O(log(n)).

Insertion complexity

In the tree code there is only one loop where the node of the root of the red–black property that we wish to restore, x, can be moved up the tree by one level at each iteration.

Since the original height of the tree is O(log n), there are O(log n) iterations. So overall the insert routine has O(log n) complexity.

Parallel algorithms

Parallel algorithms for constructing red–black trees from sorted lists of items can run in constant time or O(loglog n) time, depending on the computer model, if the number of processors available is proportional to the number of items. Fast search, insertion, and deletion parallel algorithms are also known.[5]

See also

Notes

- ^ Rudolf Bayer (1972). "Symmetric binary B-Trees: Data structure and maintenance algorithms". Acta Informatica 1 (4): 290–306. doi:10.1007/BF00289509. http://www.springerlink.com/content/qh51m2014673513j/.

- ^ Leonidas J. Guibas and Robert Sedgewick (1978). "A Dichromatic Framework for Balanced Trees". Proceedings of the 19th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science. pp. 8–21. doi:10.1109/SFCS.1978.3. http://doi.ieeecomputersociety.org/10.1109/SFCS.1978.3.

- ^ a b http://www.cs.princeton.edu/~rs/talks/LLRB/RedBlack.pdf

- ^ http://www.cs.princeton.edu/courses/archive/fall08/cos226/lectures/10BalancedTrees-2x2.pdf

- ^ H. Park and K. Park (2001). "Parallel algorithms for red–black trees". Theoretical computer science (Elsevier) 262 (1–2): 415–435. doi:10.1016/S0304-3975(00)00287-5. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304397500002875.

References

- Mathworld: Red–Black Tree

- San Diego State University: CS 660: Red–Black tree notes, by Roger Whitney

- Thomas H. Cormen, Charles E. Leiserson, Ronald L. Rivest, and Clifford Stein. Introduction to Algorithms, Second Edition. MIT Press and McGraw-Hill, 2001. ISBN 0-262-03293-7 . Chapter 13: Red–Black Trees, pp. 273–301.

- Pfaff, Ben (June 2004). "Performance Analysis of BSTs in System Software" (PDF). Stanford University. http://www.stanford.edu/~blp/papers/libavl.pdf.

- Okasaki, Chris. "Red–Black Trees in a Functional Setting" (PS). http://www.eecs.usma.edu/webs/people/okasaki/jfp99.ps.

External links

- In the C++ Standard Template Library, the containers

std::set<Value>andstd::map<Key,Value>are typically based on red–black trees - Tutorial and code for top-down Red–Black Trees

- C code for Red–Black Trees

- Red–Black Tree in GNU libavl C library by Ben Pfaff

- Red–Black Tree C Code

- Lightweight Java implementation of Persistent Red–Black Trees

- VBScript implementation of stack, queue, deque, and Red–Black Tree

- Red–Black Tree Demonstration

- Red–Black Tree PHP5 Code

- In Java a freely available red black tree implementation is that of apache commons

- Java's TreeSet class internally stores its elements in a red black tree: http://java.sun.com/docs/books/tutorial/collections/interfaces/set.html

- Left Leaning Red Black Trees

- Left Leaning Red Black Trees Slides

- Left-Leaning Red–Black Tree in ANS-Forth by Hugh Aguilar See ASSOCIATION.4TH for the LLRB tree.

- An implementation of left-leaning red-black trees in C#

- PPT slides demonstration of manipulating red black trees to facilitate teaching

- OCW MIT Lecture by Prof. Erik Demaine on Red Black Trees -

- 12345, a C# Article series by Julian M. Bucknall.

- Binary Search Tree Insertion Visualization on YouTube – Visualization of random and pre-sorted data insertions, in elementary binary search trees, and left-leaning red–black trees

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||